Simblissity

home >

L2H

The

challenge is classic. The starting point and finish are pure and uncontrived.

And accomplishment is a high on par with the alpine crags around you, soaring

over a furnace desert beyond.

For

several decades adventurous souls have sought the challenge of traveling on foot

from the lowest point in the Western Hemisphere to the highest place in the contiguous

United States. Starting at Badwater in Death Valley, California, at an elevation

of 279 feet below sea level, they test their mettle on a scorching ribbon of asphalt

highway, over mountain passes and across sere basins, and on into the shadow of

Mount Whitney, 14,505-foot king of the mighty Sierra Nevada range.

|

| Badwater

Road, near the start of the paved race route | Many

come in summer, when valley air temperatures can exceed 125 degrees Fahrenheit

(52 C), and attempt to run the 130+ mile distance, either competitively - with

outside support - or self-contained, challenging only themselves. The approach

differs with the individual, but the route is almost always the same. Over the

years, only a handful have left the highway to travel their own way "from

the Lowest to the Highest..." Introducing

the Lowest-to-Highest Route

|

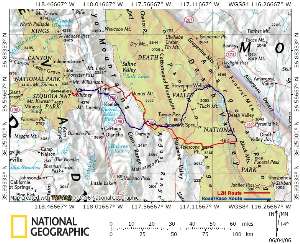

| Overview

Map - click to view full size | The

Lowest-to-Highest (L2H) is a backcountry hiking route between

Badwater and Mt. Whitney. Unlike

the traditional "race route," the L2H avoids pavement and vehicle traffic

whenever possible, in favor of a scenic, silent journey across the wilderness,

as it seeks the soul of a rugged, harsh, and ultimately beautiful land. If the

traditional approach is to complete an extreme journey on foot, then the L2H is

about living completely in a land of extremes. Indeed, this off-highway journey

encompasses even greater extremes of geography, ecology and climate, and is intended

to immerse the traveler far more deeply within the environment. In

terms of the route's layout, the Lowest-to-Highest Route represents the first

genuinely "backpacker-oriented" way to get from Badwater to Mt. Whitney.

The L2H was designed to meet the expectations of seasoned walkers looking for

a challenging one or two week trip through desert, mountain, and alpine terrain.

To this end, the route offers a number of advantages: - Provides

a sense of solitude and an opportunity for contemplation of nature away from major

roads, traffic, and other manmade intrusions.

- Travels

across scenic, interesting and varied terrain, and over a wide range of elevation

and climate.

- Follows

an efficient line of travel between its end points in order to minimize distances

between water and resupply.

- Affords

direct access to natural and developed water sources, as well as cache locations,

so as to reduce the sense of dependency or discontinuity during the actual journey.

- Returns

to civilization occasionally to facilitate resupply of food and provisions, as

well as for rest and recovery.

- Connects

to the southern terminus of the John Muir Trail and nearby PCT, offering options

for extended travel into the High Sierra backcountry and beyond.

[ top of

page ] Character

of the Route

|

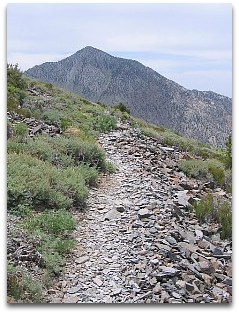

|

Telescope Peak Trail | The

Lowest-to-Highest is in fact a route - an informal, unsigned linkage of existing

trails, roads, and cross-country travel. Few established trails exist in Death

Valley National Park or elsewhere in the areas immediately east of the High Sierras

and Mt. Whitney. However, the area is threaded by numerous old roads, many of

them former miners' routes, little more than rockbound tracks in some cases. Cross-country

travel is often facilitated by the expansive desert landscapes here, which include

everything from flat, featureless salt playas, to the lightly-vegetated slopes

of arid mountain ranges, to vast alluvial fans at the mouths of canyons. And

yes, several foot trails are found here as well - some of them well-traveled and

in excellent condition, in other cases just a rough path with occasional rock

cairns to guide the way. Each of these surfaces and modes of travel come together

to make the L2H the diverse, challenging and rewarding experience it is. Distance,

Elevation & Terrain Total

mileage from Badwater to Mt. Whitney is surprisingly similar between the highway

race route and L2H route. The L2H travels a distance of about 130 miles from end

to end, compared to the race route's 135 miles. In fact the race route ends at

Whitney Portal, 8 miles and several thousand feet below Mt. Whitney's summit,

so the "peakbagging" L2H - which goes straight to the top - is comparatively

more efficient overall, at least by the mileage figures. But the more distinguishing

difference between the two routes is elevational: By seeking out an adventurous

line of travel away from major roads the L2H features a total elevation gain more

than double that of the highway route. The following elevation profiles offer

a visual comparison of the two routes. (Please note the difference in vertical

exaggeration between the two profiles.)

| |

|

| Comparison

of Elevation and Length: L2H (at left) & Race Route (vertical exaggeration

differs) |

|

Long

John Canyon, Inyo Mountains

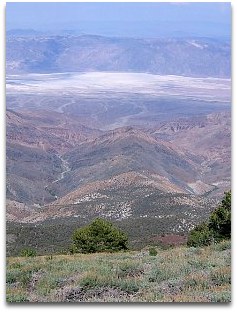

| The

difference in total elevation gain between the routes is the result of topography

and the way each route confronts it. Much of this land is at the western edge

of the vast Basin and Range province, with fault-block mountain ranges rising

sharply out of deep, wide valleys. By adhering to paved 2-lane highways that follow

the path of least resistance, the "race route" does not climb as high

nor as often as the L2H, which approaches the ranges directly, via more primitive

and steeply graded surfaces. The

L2H confronts three major ranges - the Panamints, Inyo Mountains, and the eastern

edge of the Sierra Nevada massif at Mt. Whitney - and along the way crosses Death

Valley, Panamint Valley, and the valley of the Owens River. Elevations on the

crests range from 9000 feet above sea level to over 14,500' at Mt. Whitney. Valley

elevations are much lower - so much lower in the case of Death Valley that the

climb into the Panamint Range (to Telescope Peak) represents the fourth greatest

valley-to-summit elevation gain in the United States, just behind Washington's

Mt. Rainier. In addition, east of the Inyo Mountains the L2H follows the rolling

5000' Darwin Plateau for a number of miles, with easier hiking and more moderate

temperatures. [

top of page ] Highlights

of the Adventure  Change

is seemingly the only constant on the Lowest-to-Highest. Perhaps nowhere else

on earth can a person so quickly travel on foot between markedly contrasting environments,

between worlds so far apart in character that it is hard to reconcile their physical

proximity. Change

is seemingly the only constant on the Lowest-to-Highest. Perhaps nowhere else

on earth can a person so quickly travel on foot between markedly contrasting environments,

between worlds so far apart in character that it is hard to reconcile their physical

proximity.

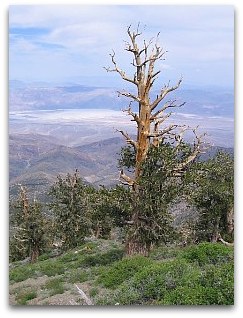

Such

is certainly the case in the journey's early miles. The route leaves Badwater

- an undrinkable saline pool - crosses the harsh, flat, and often torrid salt

playa of Badwater Basin - at 282 feet below seal level the lowest point in the

Western Hemisphere - then ascends over 10,000 vertical feet to the crest of the

Panamints near Telescope Peak, where thousand-year-old bristlecone pines thrive

in the short growing season between long, cold winters.  Or

imagine walking among desert canyons of bone-dry greasewood and endless rock,

only to turn a corner and discover the miracle of Darwin Falls. Here, a series

of perennial cascades dash among shade trees and lush undergrowth. Bird song fills

the air, punctuated incongruously with the "hee-haw" of a feral burro

hidden somewhere up-canyon, living testament to a bygone era when miners and mule

teams did heavy work here. Or

imagine walking among desert canyons of bone-dry greasewood and endless rock,

only to turn a corner and discover the miracle of Darwin Falls. Here, a series

of perennial cascades dash among shade trees and lush undergrowth. Bird song fills

the air, punctuated incongruously with the "hee-haw" of a feral burro

hidden somewhere up-canyon, living testament to a bygone era when miners and mule

teams did heavy work here.

Strange

spikey forms dot the distant horizon ahead, looming taller as the route approaches

its first stand of joshua trees, great sentinels of the Mojave desert. Their multi-armed

masses form a veritable army of green and gray across the expanse of Lee Flat,

yet make no sound to stir the utter silence of the land. Strange

spikey forms dot the distant horizon ahead, looming taller as the route approaches

its first stand of joshua trees, great sentinels of the Mojave desert. Their multi-armed

masses form a veritable army of green and gray across the expanse of Lee Flat,

yet make no sound to stir the utter silence of the land.

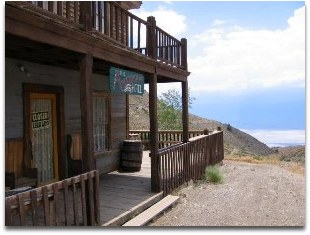

Colorful

mine tailings and even a wooden ore tramway reveal the human history of the rugged

Inyo Mountains, where the past comes alive at the ghost town of Cerro Gordo. The

American Hotel is located here, a real Old West saloon and guest house occasionally

still serving travelers today, "especially those romantics born a century

too late," says the proprietor and sole resident here at 8000 feet.

|

| photo

courtesy David Hough | Reaching

Trail Crest and the eastern divide of the mighty Sierra Nevada, you turn north

to join the John Muir Trail and walk a narrow ridge far above treeline. The sky,

reflected flawlessly in alpine lakes below, is blue and confident but the air

is thin, forcing you slowly, euphorically ahead. Ever higher you climb, past sun-cupped

snowfields, among pinnacles, to the very top of the world it seems. The summit

of Mount Whitney commands a view of peaks more numerous than all the sands in

the desert, you think to yourself. And there, below and to the east, the route

you've journeyed for more than a week slips away toward the distant horizon, back

to the sand, salt and heat of Badwater in a universe all its own. [

top of page ] Strategies

for Success Hiking

the Lowest-to-Highest Route safely and successfully requires a familiarity with

both desert and alpine environments, their particular challenges and demands,

and the equipment and techniques for dealing with them. By its very nature, the

route is neither easy nor without risk; indeed, this is a land of potential danger

beyond the norm. Furnace-dry heat, strong sun, an infrequency of natural water

sources, and rugged, steep, remote terrain are standard fare when traveling in

this harshest of desert lands, while snowpack,

cold and/or changeable weather, afternoon thunderstorms, and altitude sickness

can become concerns at higher elevations along the route. The information presented

here assumes an ability to accept and respond to such potential hazards along

the way, as well as a proficiency with the particular requirements of long-distance

hiking that involves resupply and/or backcountry caching. Do not approach the

route unprepared. Season

of Travel

|

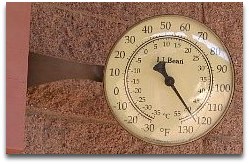

| Death

Valley digits: "a little warm" for late June |

The Badwater to

Whitney foot race occurs each year in July, typically the hottest month in Death

Valley, where the all-time high temperature record stands at an otherwordly 134

degrees Fahrenheit (56.7 C). Meanwhile, snow can fall in the high country beginning

in mid-autumn, with remnant snowpack sometimes blocking trails on Telescope Peak

into the following June, and on Whitney into July. The

upshot of these limiting factors is a narrow seasonal window in which to travel

the Lowest-to-Highest without undue hardship. In essence, the L2H is open to traditional

thru-hiking (which is to say, minus a mountaineering component) only during the

months of September and October, after the desert heat lessens and before the

early snows arrive. In most years, a start date at Badwater during the first week

of October should allow enough time to reach Mt. Whitney before ice or snow make

conditions hazardous there. Make no mistake though - the lowest terrain of the

route may still be quite warm to downright scorching, even well into October.

Other times, the weather can be chilly and inclement, including at the bottom

of Death Valley. Navigation:

Maps and Databook Because

the L2H is an unmarked, unsigned route, detailed topographic maps are absolutely

essential for navigation as well as for an understanding of the terrain through

which the route travels. To this end, we now offer a complete "navigation

bundle" for prospective hikers which includes high-resolution, annotated

topo maps, elevation profiles, and a companion databook, as well as GPS tracks

and waypoints. The maps and databook are presented in easy-to-use PDF file format,

and they can be printed either at home or using a professional document printing

service like FedEx Office. The GPS data is formatted for compatibility with most

current GPS units. Click on the following link to view and download the navigation

bundle. This

resource has been some time in the making, and we hope it simplifies the planning

process for prospective hikers. We've opted to make it available to try for free.

If you find it useful and would like to support our efforts to keep this resource

up-to-date, then please consider purchasing the navigation bundle above. The

maps, databook, and GPS info detail the main route of the L2H as well as a number

of "alternate routes" that hikers may opt to use along the way. The

alternates are typically a few miles longer or shorter than the portion of the

main route they replace; some of them may prove easier in some way, either in

terms of the terrain or logistics, while others may be more scenic or adventurous.

Refer to the maps and databook for more info. Along

with the maps contained in the navigation bundle, additional large-area overview

maps can also prove helpful in finding your way. The DeLorme California Atlas

& Gazetteer offers a broad perspective of the terrain, including roads leading

away from the route toward developed areas where assistance would be available

if needed. Trails Illustrated produces a folded, waterproof map of Death Valley

National Park, with numerous secondary and primitive roads and even some trails

and x-c routes depicted. Additionally, the entire L2H route is covered (without

actual route depiction) in 1:100,000 scale detail on four maps produced by the

BLM. Visit the Public

Lands Interpretive Association website to order the BLM's Death Valley Junction,

Darwin Hills, Saline Valley, and Mount Whitney surface management maps.

Locating

Water With

an average annual rainfall of less than 2 inches, coupled with high temperatures

and low dew points, Death Valley defines aridity in sharper terms than almost

anyplace on earth. Yet the ranges that rise so prominently above Death Valley

and surrounding basins do capture precious moisture from occasional weather systems,

draining it into the basins to evaporate in salt pans or well up in unusual, unpotable

ways as at Badwater. These ranges also retain some of their moisture, as evidenced

by their more abundant flora and fauna. And in a few places this vital water runs

at the surface, clear and drinkable. A

lack of abundant natural water sources is a fact of life on the Lowest-to-Highest

Route, at least before reaching the Owens Valley at the edge of the well-watered

Sierra Nevada. In its desert reaches, hikers will at times need to carry a considerable

amount of the wet stuff - perhaps several gallons - and walk with a purpose from

one known source to the next.

|

| High

desert surprise: goldfish in China Garden Spring | The

L2H route has been carefully laid out to make the water situation as manageable

as possible for experienced desert travelers. Several natural sources are encountered

along the way, of which a few are fairly dependable. Developed water is also reached

at intervals throughout the route, and can generally be counted on during the

normal hiking season. The L2H Navigation Bundle includes a water summary which

is periodically updated based on reports from hikers along the route. It also

lists potential on-route cache locations, where one could leave a supply of water

beforehand to be picked up during the hike. (See the following discussion.) | | VIEW

AND PRINT THE WATER SUMMARY HERE |

Water Caching At

first glance, the above water chart may seem to indicate that water caching is

unnecessary on a thru-hike of the L2H. And for experienced desert hikers willing

to pack heavy water loads, it may not be necessary. But for safety's sake more

than mere convenience, all hikers, regardless of ability or inclination, should

at least consider caching some water along the route.

|

10k vertical feet cross-country elevation gain | Three

areas of the route in particular suggest the benefit of water caching: the western

and eastern base of Telescope Peak, and the long stretch without surface water

west of China Garden Spring. The climb of Telescope Peak's ridge is steep, extremely

long (10,000+ feet of elevation gain), remote, and mostly cross-country. Although

Hanaupah Spring to the east is considered reliable, what happens if your arrival

is delayed by the unexpected? Or what if the springs in Tuber Canyon happen to

be dry when you're absolutely counting on them? To be caught on either side of

the mountain with empty water bottles could very easily prove disastrous. Water

caches left at nearby road crossings would provide a margin of safety, and make

this challenging ascent and descent much more manageable, especially as the caches

would permit a more deliberate pace in difficult terrain. Water left near the

entrance to Hanaupah Canyon at the western edge of Badwater Basin would also help

to ensure a safer and more enjoyable crossing of this lowest, hottest, driest

region at the very start of the route. Setting

up a last minute water cache on the route about 7 miles west of China Garden Spring

would be fairly straightforward. Upon reaching the store at Panamint Springs,

one could purchase water in plastic jugs and then hitchhike 12 miles west along

the highway to its next intersection with the L2H route. There, the hiker could

hide the water nearby in desert brush, then hitch back to Panamint Springs and

continue along the route, retrieving the cache on foot in a day or so. (And being

sure to pack out all supplies from the cache!) Additional

water caches would require more targeted vehicle assistance. For those with no

outside support, one tested solution would be to rent a car in the town of Pahrump,

Nevada, 1.5 hours east of Death Valley National Park. This would be done prior

to arrival at Death Valley, for example if flying into Las Vegas beforehand. After

placing the water caches, one could either return to Pahrump and then hitch back

to the Death Valley area, or potentially arrange to have the vehicle picked up

by the rental company for an extra charge. In this last scenario hikers could

arrive at Badwater under their own power and start the hike on a schedule of their

choosing. Resupplying

| |

Welcome

to Panamint Springs Resort (just around the bend) | The

Lowest-to-Highest Route offers two potential opportunities for resupply along

the way. Packages of food and supplies can be shipped to Panamint Springs Resort

(with prior permission) and the town of Lone Pine prior to the hike, then picked

up along the way. The route heads directly through both localities. Although

the Panamint Springs resupply may not be truly necessary on a hike of this length,

it can still be helpful in terms of reducing overall packweight; by minimizing

the weight of food supplies, it becomes easier to carry the heavy loads of water

which are sometimes unavoidably necessary. Panamint

Springs Resort has a campground, motel, restaurant, and small store with mostly

snack items. Maildrops may be held at the discretion of the proprietor, and must

be shipped via UPS only. Call to confirm details: (775) 482-7680. Be sure to mention

that you'll be hiking through Death Valley and give an approximate date of arrival.

For best odds when calling, you might also plan to reserve a motel room for when

you'll be passing through. Lone

Pine is a small, tourist-oriented town with most services available, including

a medium-sized grocery store. Sending a maildrop would probably be unnecessary

if heading west toward nearby Mt Whitney, but might be helpful if intending to

continue on the JMT beyond Whitney or if hiking eastbound on the L2H toward Badwater.

The Lone Pine post office (zip code 93545) accepts packages addressed for general

delivery. A small

store is also located at Whitney Portal at the base of the Mt Whitney Trail. The

store sells snack items and has a grill with limited menu options.

Permits

|

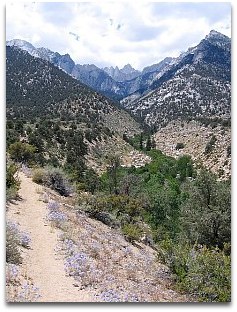

Whitney

Portal National Recreation Trail,

en route to Permit Country |

In its final 8 miles

the L2H ascends Mount Whitney via the main Mt. Whitney Trail and John Muir Trail.

Due to the extreme popularity of hiking Mt Whitney, access to the summit and summiting

trails is available by permit only. A lottery is held each spring for reservations

to hike Mt Whitney in the current season. Lottery winners (typical odds of success

are only 25-30%) then pay for a specific entry date (their preferred date, else

an alternate). Any dates that remain after the lottery are then made available

to the general public on a first come, first served basis. In the past, the possibility

existed to obtain a "walk up" permit at the Inyo National Forest office

in Lone Pine. This option is no longer available, and all permits must now be

obtained online via the Recreation.gov

portal. During

the peak hiking season in July and August permits to enter the Mt. Whitney Zone

from Whitney Portal are generally all reserved well in advance, and permit openings

due to cancellations - although possible - are less likely at this time. September

and October can pose less of a concern, although L2H hikers will still benefit

from being as proactive as possible in searching for any available permit date

and then timing the journey around that date, within reason. "Non-quota season"

extends from early November to late April each year, meaning no limits are placed

upon entry during this time, with the earlier portion of this season increasingly

in play due to climate change, albeit one should always be prepared for winter

conditions near the summit at this time of year. [

top of page ] The

Route In Abstract From

Badwater (279 ft below sea level), the L2H heads west across Badwater Basin to

Hanaupah Canyon, where it follows 4WD road to Hanaupah

Springs. [e.g., 1st camp] It then proceeds cross-country to

Telescope Peak's ridge (10,000 ft), northbound via the Telescope Peak Trail, then

west x-c into Tuber Canyon. An old track in Tuber Canyon passes a few potential

springs, [2nd camp] and continues downhill

to Wildrose Road (2500 ft), where the L2H joins faint dirt tracks northwest to

sere Panamint Valley and the village of Panamint Springs,

with food and water available (el. 2000'). [3rd camp: motel or campground]

Scenic, perrenial Darwin Falls and China

Garden Spring lie southwest of Panamint Springs, which the L2H

approaches before proceeding cross-country on rocky, volcanic slopes through the

untracked Darwin Falls Wilderness [4th camp] to a junction with the Highway

190 "race route" (4800'), then north via Saline Valley Rd toward Lee

Flat joshua tree forest (5500'). From a road junction along the historic White

Mountain Talc Rd (4900') [5th camp], the L2H climbs westward to the living

ghost town of Cerro Gordo along the rugged Inyo Mountain crest, then turns north

on 4WD to Mexican Spring (9200') and the

ruins of the Saline Valley salt tram. A vague, cairned trail heads west downhill

in Long John Canyon, past a possible spring

(5800') [6th camp], and into the Owens Valley via Lone Pine Narrow Gauge

Rd to US 395 and the town of Lone Pine. (3700')

[7th camp: motel] Here the L2H joins the Badwater-Whitney Portal roadwalk

route for part of the way up Whitney Portal Rd, but leaves it for good at Lone

Pine Campground (5900') to follow the Whitney Portal National Recreation

Trail. The route is concurrent with the Mt Whitney Trail from Whitney

Portal (8300') [8th camp: Whitney Portal Campground walk-in backpacker

campsites, reservations required]

to Trail Crest, then follows the John Muir Trail to its terminus at Mt Whitney's

summit.  Death

Valley Weather Forecast Death

Valley Weather Forecast

Current

snowpack at 11,400' near Mt Whitney Current

snowpack at 11,400' near Mt Whitney

[

top of page ] L2H

Interactive Map Take

a virtual tour of the Lowest to Highest Route with Google Maps. The following

interactive map illustrates the route of the L2H (in red) as well as various alternate

route options (blue). Toggle betwen a traditional map view and satellite imagery

for an informative look at the varied landscapes through which the route passes.

L2H

on Instagram  | Cam

"Swami" Honan, Ryan "Dirtmonger" Sylva, Joshua "Bobcat"

Stacy, and Greg "Malto" Gressel

after finishing their L2H thru-hike.

(Photo by Cam Honan) |

#LowestToHighestRoute

| #LowestToHighest

| #L2HRoute

|

#LeaveNoTrace

| #PackItInPackItOut

Please

do your part and do not leave anything behind after your hike, including

all water / supply caches. These will otherwise become litter. We,

as well as DVNP, the BLM, and Inyo NF, appreciate your help. Click

here for more info.

[

top of page ]

Copyright

© 2025 simBLISSity Ultralight Designs  |

|