Trails

& Terrain

| Mileage

by Surface Type |

| Foot

Trail | 425 |

56% |

| 4WD

dirt | 145 |

20% |

| 2WD

dirt | 85 |

11% |

| X-country |

85 |

11% |

| Paved |

30 |

2% |

| Total

770 |

On

any given hiking day along the route, you can expect to encounter a variety of

conditions and surfaces underfoot. As mentioned elsewhere, the G.E.T. consists

of existing hiking trails, 2-track/4WD roads, improved roads, and cross-country

travel. The route makes use of these surfaces according to their availability

in the journey's grand scheme, with an emphasis on providing as often as possible

a wilderness experience, with superlative scenery, interesting surroundings, a

quiet and contemplative ambience, and ample access to pristine camping opportunities

as well as water. Efficiency of travel between town stops is also a priority in

the G.E.T.'s routing, although places of particular interest have sometimes merited

a more circuitous routing.

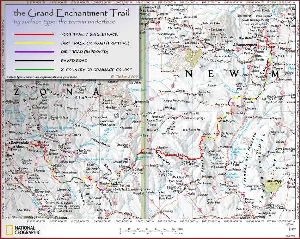

Map of Surface Types - Click

to view full size

Trails

Hiking

trail accounts for a bit over 400 of the G.E.T.'s total miles. Some trails or

portions of trails are well used (typically by hikers or equestrians) and/or regularly

maintained. These are generally easy to follow without referencing map or guidebook.

Other trails receive less visitation or infrequent trail crews, and may have occasional

or frequent brush growing on or over the path, eroded or unstable tread, and/or

occasional downed trees and limbs. These conditions are most often encountered

in designated Wilderness areas or other remote portions of the route. Also, in

areas affected by fire. Many of the trails the G.E.T. uses fall in between the

two extremes, or vary in condition from place to place. Depending on the obviousness

of the trail's direction of travel, any impediments to travel may require only

due care or a brief walk-around, or else they may require the use of map, compass,

GPS, and/or the guidebook information to determine how best to proceed. In a few

brief cases, trail tread has not yet been constructed (or has reverted to nature),

but the intended direction of travel is marked with rock cairns, flagging tape,

and/or tree blazes (bark cuts).

|

| Opposite extremes:

Excellent trail in the Superstitions of Arizona (above); brief stretch of trail

damaged by wildfire in New Mexico (right) |

Grading Standards

Most

trails encountered are reasonably well graded, often climbing and descending steeper

slopes via gentler switchbacks. Standards obviously vary from region to region,

just as with overall trail conditions. Since the route makes passage over more

than a dozen mountain ranges, total elevation gain and loss is fairly significant

(though not nearly so aggressive as along the Appalachian Trail, for example).

However, because maximum elevations are fairly modest (below 11,000'), and since

days of climbing are often followed by days of relatively gentle terrain, overall

strenuousness of the route can perhaps best be described as moderate. (Elevation

profiles of the route suggest roughly 104,000' of accumulated elevation gain over

the full route distance. See overview

profile.)

2-Track

/ 4WD Roads

|

| Quiet 2-track road

in Arizona's Turtle Mtns |

These

are the most primitive of road surfaces encountered. Totaling about 145 miles

of the entire route, 2-track / 4WD roads are also the most common type of road

feature. The term "2-track" derives from a frequent characteristic of

such roads - a pair of tracks, or ruts (grooves), with a raised and sometimes

rocky or brushy area between them. Four-wheel drive vehicles are the usual "maintainers"

here, although in many cases the road surfaces are too rough or steep for most

vehicles, if they're open to the motoring public at all. For our purposes, 2-track

and 4WD refer to any road surface too challenging for 2 wheel drive vehicles such

as passenger cars. These roads are often quite enjoyable to walk on - narrow,

rugged and interesting, with nature close at hand - yet they also are mostly straightforward

and easy to follow, allowing for steady forward progress. In the vast majority

of cases, you'll have these roads to yourself and will not encounter vehicles.

(Weekends during fall hunting season can be an exception in certain places.)

|

| Priest

Canyon Rd, Manzano Mtns, NM |

Improved

Roads

Any

road maintained to a standard that would permit passenger cars is here considered

to be "improved." These surfaces may be dirt or gravel (~85 miles of

the route) or pavement (30 miles). Often encountered in areas away from public

land, these roads sometimes serve as the legal rights of way that lead the route

through towns or between parcels of Forest Service, BLM, or state land. As with

2-track roads, these improved roads occur sporadically over the course of the

route, so that any given day of hiking might subject you to only a few such miles,

if any. Forward progress is well facilitated by such roads, and most do not carry

much vehicle traffic, so the walking is pleasant and easy. You can also use such

roaded portions of the route to help stay on schedule, for example if a recent

section of challenging singletrack trail caused you to travel more slowly. (The

GET topo maps and guide explain in greater detail where each surface type begins

and ends.)

Cross-country

Travel

Cross-country

travel accounts for approximately 85 miles of the suggested G.E.T. route, and

is generally of two forms: drainage course walking and line-of-sight travel in

open desert.

|

| Cross-country

in Johnny Creek Canyon, AZ |

In

the first type, which occurs more commonly, the route follows along the bottom

of a dry creek bed or "wash" in order to link with road or trail at

either end. Sometimes the wash may in fact be a flowing creek, such as in a steep-sided

canyon environment, and in this case you would normally travel the path of least

resistance along the creek bank, fording to the other side whenever necessary

or convenient.

Examples

of drainage course walking include Putnam Wash (Segment 5), which is wide, dry,

sandy, and obvious; Aravaipa Canyon (Segment 7) - follow the creek bank until

the canyon wall forces you to ford, then follow the other bank, etc.; and the

Abo Canyon area (Segment 34), which is a network of steep-sided sandstone arroyos

that the route follows rather like hallways, turning the "corner" as

one ends at the intersection with the next. Drainage walking can be interesting

and adventurous, often rugged and wet, but the route has been designed to make

these sections efficient and straightforward as well. Basic routefinding ability,

patience (expect a pace no faster than 1 mph on occasion), and a willingness to

pioneer are the only real prerequisites for this type of travel. (Please note

that cross-country travel along the G.E.T. is not bushwhacking -

fighting through tree limbs and high brush in disorienting terrain - although

the surfaces underfoot can sometimes be quite rocky, sandy, wet, or overgrown.)

Line-of-sight

travel, aka "following a bearing," can sometimes be more challenging

than drainage walking because of the need to avoid obstacles without veering away

from your objective. However, the G.E.T. employs such travel only rarely, and

only in open terrain where the walking is mostly easy and free of obstacles, and

where a visual bearing is easy to obtain. One example occurs in open desert east

of New Mexico's Black Range, (Segment 27) where the route leaves a dirt road (indicated

by flagging and GPS waypoint) and proceeds downhill on a bearing to cross a wash,

(GPS waypoint-marked location) then continues on to join another road by a windmill

(GPS waypoint). Several different approaches to navigation are possible here.

One is line of sight, where you would simply hike downhill to join the obvious

wash at a random location in its canyon, then walk alongside the wash itself,

keeping a sharp eye out for the windmill, and finally leave the wash on a bearing

to the windmill. A more direct approach would be to follow a compass bearing the

entire way, as determined by map, possibly adjusting your exact route here and

there as dictated by the terrain. Still a third way of navigating here is by GPS,

walking from one waypoint to the next, more or less emulating the non-linear but

perhaps easier route that the author actually walked. None of the G.E.T.'s few

overland excursions requires advanced routefinding ability, however it is recommended

that hikers have a good understanding of how to navigate by map (especially) and

compass, as well as GPS (as an additional technique, not a substitute).

|

| Cross-country

near Dusty, NM |